To many, a windsurfing mast is a non-essential, something you pick up for cheap on an online market place, the most amount of carbon for the least amount of money. Well this feature might just get you thinking that perhaps this is not the best method of mast selection. The mast makes up the skeleton of our windsurf set-up and without it we certainly would be significantly closer to being just paddle surfers rather than windsurfers, more importantly with it we have a structure that allows us to be propelled by the wind at speeds in excess of 50 knots! So the question is what mast should you have and what is the point in this feature? Well the answer to the former is easy, it is to give you, the reader, an idea on why brands insist that you use their masts for their sails. Is it all just money making or is there really some truth behind what we are told. So who better to ask than Ken Black, Peter Hart and Roger Tushingham himself, three of the big dogs at Tushingham HQ who really REALLY know their stuff when it comes to windsurfing gear.

Considering as Tushingham have a great reputation for masts and have been in the industry well before many of us were even speaking the word mast, we figured we couldn’t go too far wrong when we proposed to fire a few questions their way. However, before we dive in it is important to know a thing or two about the basic mast principles.

Stiffness

A windsurfing mast must have an overall stiffness within the range specified by the sailmaker for any given sail.

Stiffness is measured by supporting the mast at each end and applying a 30kg weight to the middle. The mid-point deflection figure is applied to a formula that takes account of the mast’s length to give an IMCS number (Indexed Mast Check System) The bigger the number the stiffer the mast; IMCS numbers typically range from about 11 (soft junior mast) to 36 (stiff race mast).

Bigger sails need stiffer masts to support the extra forces so it’s normal for longer masts to be built stiffer with higher IMCS numbers.

Thanks to the geeks at Tushingham HQ we have the formula for calculating IMCS:

IMCS = Length(cm)3 / Mid Point Deflection(cm) x 216225

Bend Curve

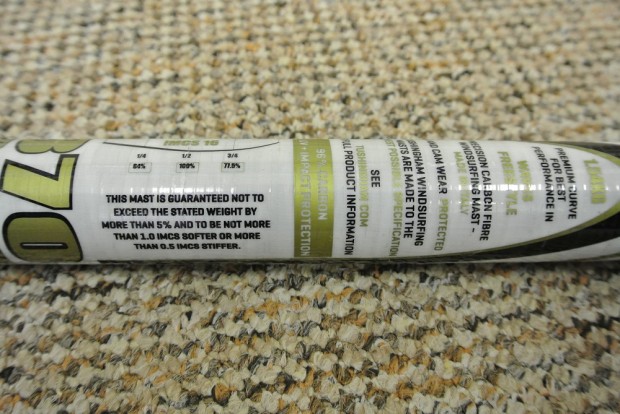

Stiffness does not tell the whole story. The shape of the bend curve is also important; we’ve all heard terms like ‘constant curve’ & ‘flex top’ but what do they mean? In fact, these are quantifiable terms. When we measure the half height deflection for the IMCS test, we also measure deflection at the quarter and three quarter height points. We express these as a percentage of the maximum deflection, for example here are the test results for a ‘constant curve’ 460cm IMCS 25.

- Maximum deflection at ½ height = 181mm (which calculates to IMCS 25 on a 460cm length)

- Deflection at ¾ height = 138mm which is 76% of maximum deflection 181mm

- Deflection at ¼ height = 116mm which is 64% of maximum deflection 181mm

The bottom half of the mast is always stiffer than the top. If we subtract the ¼ height percentage from the ¾ height percentage we get; 76 – 64 = 12. This mast has a bend curve number of 12.

The industry standard terms describing windsurfing mast bend curves are:

- 0-6 = Hard top

- 7-9 = Hard Top/Constant Curve

- 10-12 = Constant Curve

- 13-15 =Constant Curve/Flex top

- 16-18 = Flex Top

- 19-21 = Flex Top/Super Flex Top

- 22+ = Super Flex Top

The higher the number the more flexible the mast is in the upper half relative to the bottom

The mast in our example just falls into the ‘Constant Curve’ range and can be described as a 460/25 Constant Curve with a bend characteristic of 12.

If you are interested in finding out even more details then we strongly recommend you follow up this read with all the information on tushingham.com/windsurfing/masts

Chatting with Ken Black (KB), Peter Hart (PH) and Roger Tushingham (RT).

BOARDS: Why is it important to have the right mast?

KB – It is fundamental to the way the sail works.

PH – It’s worse than fitting cheap remould tyres to a F1 car. You’re completely undermining the sail’s potential.

RT – Unlike a yacht mast, which is controllable, a windsurfer mast is completely unsupported; it either fits or it doesn’t, simple.

BOARDS: What is the right mast?

KB – A stiffness that suits the sail size and a bend curve to suit the sail’s luff curve.

PH – Every sail-maker cuts the luff curve around the bend of a certain mast – usually the one they sell funnily enough. That is the mast to buy. Having said that, especially with allround sails, they’ll try and make it compatible with as many masts as possible and will recommend which ones work. The generic labels ‘flex top’ and ‘constant curve’ are a guide but outfits don’t all agree on what constitutes a constant curve.

RT – You can find a full a explanation of bend curves on the Tushingham website. It’s not rocket science but well worth taking the time to understand, then you can make the right choice.

BOARDS: What happens if you have the wrong mast, and should weight really be something to worry about?

KB – The wrong mast will alter the way the sail works and feels. For example: a mast that is too stiff will make the sail stiff and unbalanced, too soft and it will feel spongy and slow. The wrong bend curve will alter the height of the centre of effort: too stiff in the top will pull the sailor off balance, too soft in the top will lose bottom end power. Weight effects the flex response and handling so it is significant but stiffness and bend curve are more important.

PH – YES! Worry like hell. As I never tire of telling people on my clinics, good technique stems primarily from good power control. If you’re fighting the rig, you’re going to be defensive, tense in the back seat and in the worst shape to initiate a manoeuvre. There is no better way to make a sail fight than shoving the wrong mast up it. If it’s too stiff, especially in the head, it won’t exhaust and feel heavy and ‘draggy’ and be very difficult to over-sheet and depower. Too soft and it will feel spongy, undirect. Gusts will blow through you and it will break up under load and feel unstable.

WEIGHT is a big issue. The lighter it is, the quicker it returns as you pump and so the earlier you plane and the more responsive and reactive it feels – which is key in gusty winds and wild seas. If you have extra cash burning a hole in a pocket, spend it on a higher carbon content mast before anything else.

BOARDS: What are the different types of mast and how do they work?

BOARDS: What are the different types of mast and how do they work?

KB – Flex top masts are good for top end speed and stability. Constant curve good for all round performance. Stiff top masts are only used for light winds, usually racing.

PH – RDMs (reduced diameter) are the popular choice for wave and freestyle sails. The over-riding advantage is that their thicker walls make them stronger. The payback is that there’s less air in them so they sink faster. The first time I used one was at Hookipa. Off the rocks I suddenly noticed how much quicker the rig sank. I couldn’t release it in time and got trashed. I’m over it now. For sails designed more with speed in mind, the SDM (standard diameter) tends to work better. Being more flexible in the tip, the sail stays fuller and more locked in below the boom and twists off more – perfect for sailing over-powered at high speeds.

BOARDS: How do you test for quality control and where do the masts come from?

KB – (Roger’s dept)

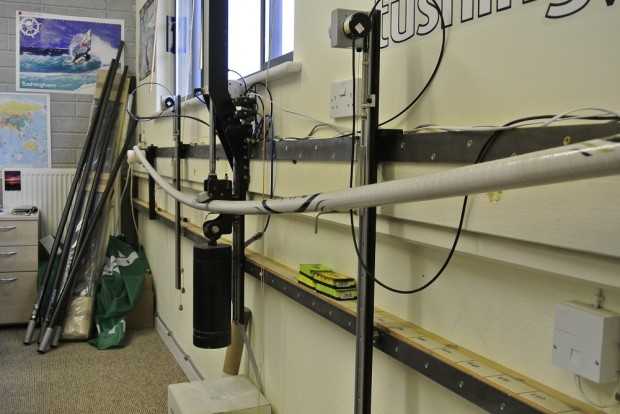

PH – Tush are one of the few companies who actually have a machine that checks the bend of each mast. It came to our attention some time ago how much variance there was in masts all purporting to be same bend!

RT – We test all masts to make sure they’re within tolerance for overall stiffness and with the correct bend curve. Laminate quality is harder to test on a finished mast; we control these factors by careful control of materials and specification and with physical checks during the production process. Tushingham masts are made in Italy, a country that was early into pre-preg carbon technology as part of its cutting edge fishing rod industry.

Quality Control Video Demo

BOARDS: What should people watch out for in a poorly selected mast?

KB – This is a quality issue. When the mast is new it is difficult to spot weaknesses so reputation and warranty are important. In used masts check for impact damage and dry laminate areas.

PH – It is indeed a problem that carbon masts often show no visible signs of weakness. Often the J.S.A. (Just Sailing Along) breakages result from a previous impact. Perhaps you dropped it against the pavement/head-butted it last time out, which fractured some of the fibres. Top tip especially with a new mast, is to keep the first runs close to shore and do some vigorous pumps. If the mast has a weakness it will usually break straight away. Look out for signs of impact. On racier masts, over-tight cambers can rub away the outer fibres and cause a weakness.

BOARDS: All masts can break but what is done to prevent them from doing it as much as possible?

KB – Avoid impact damage, & limit u.v. exposure. If cams are used make sure the cams are working properly and are not causing wear to the mast. Masts have a reinforced area for the boom attachment, it is important the boom is attached within that area.

PH – Don’t drop them! Especially not in the heavy waves of a shorebreak! It’s the shock loads that do the damage. Commonest is where the mast on the shore side of the wave. The wave picks the board up, drives the mast tip into the shingle and then breaks. Secondly it’s when the rig gets caught right in the lip of a pitching wave. When the wave breaks it suddenly bends the mast like someone cracking a whip. Top tips are to get the mast tip pointing out to sea and sink the rig under the wave where the waters are stiller.

RT – We started fitting an outer layer of white glass fibres a few years ago. This keeps the mast cool in hot sun and reflects UV, it also offers some protection to the outer carbon fibres which is important in reducing the possibility of concussion damage.

BOARDS: I’m a fairly new freerider, what mast should I take with my 6.0 and 125l board?

KB – Usually it would be a 430/21 with whatever bend curve is recommended by the designer.

PH – So much depends on the age and design of the rig. I’d obey the recommendations on the sail. If it’s suggesting an IMCS range (for a modern 6.0 it might be 19-21), go for the softest option.

RT – Obviously the stiffness and bend curve should suit the sail. Beyond that it’s a question of weight; a super light high carbon content mast is just as beneficial to the new free rider as the hardened pro’. It depends on the depth of your pockets!

BOARDS: I’m getting into waves what mast should I take with my 4.7 and 90l wave board?

KB – Usually 400/19 but on some sails a lighter sailor might prefer to use 370/16. The main decision is usually SDM or RDM. RDM will bend further before breaking so is more likely to emerge in unscathed from a big wave, it’s easier to grab hold of at the boom cut-out too. SDM have better floatation so are easier to recover from longer submersion. Generally they give a lower centre of effort as the lower section stays stiffer under load so produce more speed and stability in high winds.

PH – I’d go RDM. Again look at the recommendations. For a 4.7 it’s likely to be a 370/16 or 400/19. One thing to add is that some small sails have adjustable head turbans to save you money and allow you to get away with a longer mast. BUT the sail will feel hard and unforgiving. The best way to widen a small sail’s wind range and make it soft and forgiving is to fit the shortest, softest recommended mast.

BOARDS: I’m a top pro freestyler, what mast should I take for my 4.2 and 90l freestyle board?

KB – 370/16. Whether RDM or SDM is personal preference. RDM is easier to grab hold off and gives a different feel to the more solid feel of the SDM which is also a little lighter.